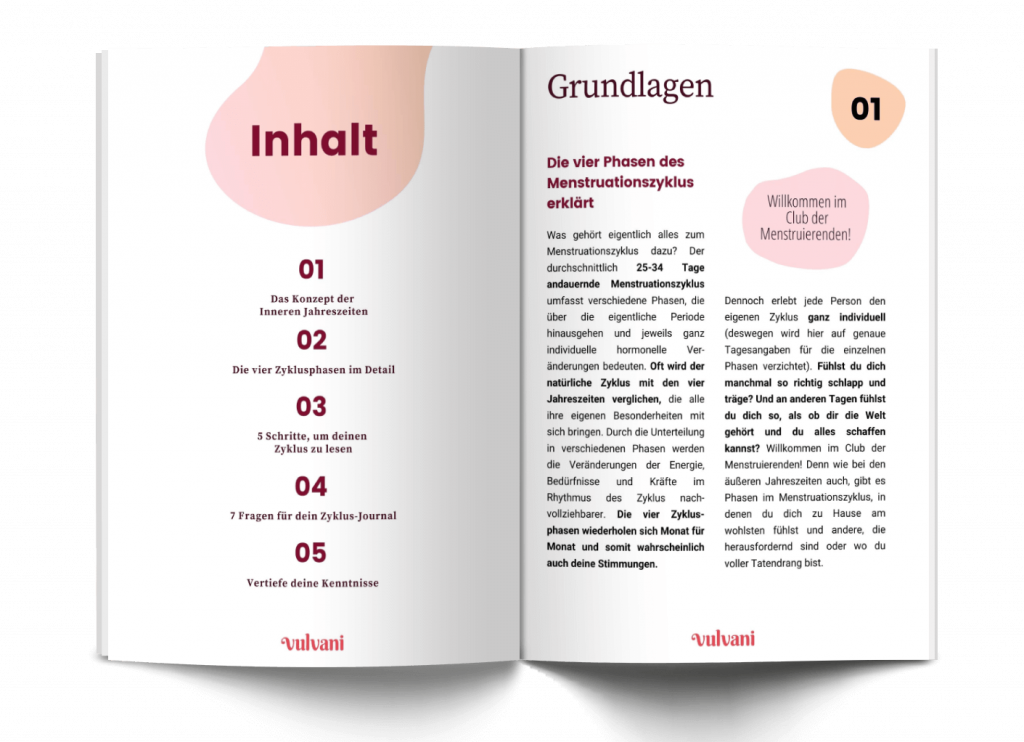

Discovering your menstruation as a spiritual practice

Yasmine understands her menstruation as a spiritual practice and shares in this interview how she is connecting more with her own body through cycle awareness.

Sex is a natural part of society, but sex education is so often found to be lacking. This affects people throughout their lives, but particularly young people who are experimenting and having their first sexual experiences. Lilan, an Education Studies student from University College London, reframes this discourse. Instead of treating sex education as being about the delivery of hard facts, she believes sex education should be a conversation. The project she organised, b.zine, a zine about sexual health and experiences, brings this to the fore.

I’m a university student, but also an aspiring sex educator and a creative thinker. My main passion is being able to combine those things, so education and creativity sit at the core of my projects. This is a really interesting way to recalibrate sex education, because usually it’s very regimented. It’s just a list of facts poured into young people’s heads. And then they’re asked to walk away and go out into the wide world to figure it out for themselves. But mixing it all up with creativity, I found, is a really cool way to redefine what sex education can be. That’s where my project, b.zine, came from.

When I was sixteen, I started having my first sexual experiences, and quickly realised how unprepared I was. I was going in totally blind, with no institutional support, and no information on how to navigate this exciting but terrifying new world. Not only did I lack awareness of the risks, but also awareness of the pleasure and beauty I should be looking for. It turned out okay: I was lucky enough to have those experiences with really kind, good people. But a lot of people were in the same position, having to feel their way through. That sparked the thought: why does no one speak about this? Why isn’t there that dialogue – an educational dialogue, but also a social dialogue? So from then on I got really passionate about it and would research it. I read books on sex education, but also on feminism, culture and community, and LGBTQ+ experiences.

That was another catalyst for my passion: I came out as queer when I was 17 or 18. I felt really isolated in that experience. There was no dialogue about the normality of my sexuality in school or in public discourse. I felt really confused and torn about it and constantly invalidated by different sources. So, I wanted to create something that provided a space for autonomous voices, so young queer people could speak up and tell their own stories. My sexuality, in all its definitions, instigated my passion for this.

I had been going to this clinic, the Brandon Centre since I was eighteen. It covers both sexual health and mental health, and I think the intersection there is really important. When I was starting on b.zine, I reached out to them to see if they’d help. They took me on and mentored me. They’re very oriented around young people and put our voices at the core. I worked with them to develop a young people’s leadership board, which enables young people to have an influence in how the organisation is run.

We also ran focus groups with young people who had used the services, in order to get feedback on the clinic’s work. I particularly wanted to seek out LGBTQ+ people and their experiences in sexual health clinics. We found there are a lot of assumptions made by staff, such as assuming patients’ gender and assuming who you will be having sex with. Overall, treating the experiences of cisgender, heterosexual people as expected. We got to give feedback on what we’d found to the people in charge of the clinics in the area, so they could take action on the information. Next year, we’re looking to change how we campaign and expand outreach, either through social media or posters and leaflets.

b.zine is a zine about sexuality, sexual health, and sexual identity. But it’s not sex education in the traditional way. As I mentioned earlier, I think the problem with institutionalised sex education is how it’s just about dishing out facts. I wanted to approach it how they approach it at the Brandon Centre: everyone in the space is both a teacher and a learner. Everyone holds valid and powerful knowledge about their own experiences, but no one knows everything there is to know. So it’s much more about dialogue than teaching. It hasn’t been tailored to be politically correct or tiptoe around sexual health issues.

I’ve always loved print media, art, and creativity. Just having tangible things to hold in your hands and connect with. It was my dream when I was sixteen to create a sexual health zine. Zines are a great way of producing media accessibly and cheaply. They’re quite an anti-authoritarian, anti-normative form, that distributes new ideas without having to be approved by institutions like publishers. We print it ourselves and distribute it ourselves. I was already really inspired by that rawness. So when lockdown hit, I was bored after all my work for university was cancelled. I’m the sort of person who always needs a project to work on. I pitched b.zine to my university volunteering service and got funding, built a team, and got it running.

Because I was the founder of the project b.zine, at first it involved everything. I did all the roles for the first few months. Project manager, social media manager, wellbeing monitor, all these different branches I had to juggle. It involved a lot of planning, a lot of forms, a lot of budgeting. For a while it was reaching out to schools and clinics to find support, so I could learn from them as well. Then it involved coordinating people, making sure jobs were done, that everyone was enjoying themselves. There were lots of meetings and dialogues about our plans for the project. So, the first year was just about organisational stuff, as I and my friend Zoe organised the whole thing.

Then we were designing workshops, too, which was my favourite bit. We brought people in to design the workshops, making sure they mirrored our central ethos about co-production instead of teaching. It was a lot of learning about how to manage something, which I’d never done before. It was creative in that way: trying to bring something to life, from scratch.

It’s very subjective. I feel that with sexuality and intimacy, subjectivity is key. Your personal experiences, experiences with different people, and how your body changes throughout your life, are all very different. I wanted to challenge how we talk about sex normatively through education, and generalisations about straight or gay sex. There’s a lot that young people can teach older generations as well, about sex and what it means to live in your body. Everyone has their unique story that is totally their own, so to resist these generalisations I wanted to let people tell them. Art was a really nice way to do that. There are no rules in art, no right or wrong way to say it. I didn’t want to mediate anyone’s stories or make them fit in a box.

Most people nowadays can think that in order for something to be worthy of attention, it has to make money. It has to be widespread. I wanted to avoid falling into that trap. It can be really toxic and harmful when measuring your own success, especially creative endeavours. The impact would be satisfying for me whether it helps one person or five hundred. If one person comes to me and says, “That was a beautiful thing to read,” that’s enough. At the time of this interview, we haven’t even distributed it fully yet, but the impact has already been wonderful. Just within the team itself, the atmosphere we’ve created is fantastic. People have developed their ideas on their own bodies, partners, and sexualities, as well as what they want to do in the future.

I came into my degree thinking that sex education would heal everything in our culture. But since studying Education Studies, I’ve developed a better understanding of the limitations of education. I don’t want to fall into the trap of the ‘education gospel,’ where education is seen as the universal solution. It is a powerful thing, but we should recognise other way change can occur, like how human relationships can cause change.

Sex education can have a massive impact on self-love and expression. It’s incredibly important. But we can improve our relationships with ourselves, our sexuality, and our pleasure outside of the borders of institutions. We can have these discussions and discourses in culture and wider society as well. I’m still trying to figure this out, but education is just the starting line. It’s a vital part of reforming our relationships with our bodies, but it is still a part, not the whole.

Though I started with a rigid idea of sex education, my journey has given me a completely different outlook. It’s been about understanding myself and constantly unpicking my biases and thoughts, learning to never take things for granted. Never be uncritical of ideas and assumptions. I’ve been learning an exciting new way of being a thinker, with a new understanding of the importance of sex education. It has really affected my own relationship with my body, which I’m super grateful for.

Keeping up with b.zine. It’s still running, although I’ve taken a step back to look after my mind and body. I want to keep this thread of creativity and rethinking educational relationships going, and engage in creative writing myself. Another zine project I got involved with was one in collaboration with the Refugee Council about refugees. I wanted to create a discussion around that as well. I also recently got a job with the Brandon Centre as a mentor for young people about sexual health. This has all been an amazing experience, and I’m excited to carry it forward. I’d like to keep doing what I’m doing, in new ways.

Yasmine understands her menstruation as a spiritual practice and shares in this interview how she is connecting more with her own body through cycle awareness.

What options are there for male birth control? Ailsa delivers an overview of what is available now, and what may come in the future.

Sustainable underwear? The founders of TUKEA talk about fair labour conditions, body diversity and body literacy.

…and empower countless women to make empowered choices about their bodies!